In the early part of 2012 there was a bit of a row going on about the Galway city council's decision to celebrate Che Guevara's

roots from the Galway Lynch side of his family. The council voted unanimously to place a memorial to “Che” (nickname for

friend or buddy) Guevara near Eyre Square in their city center.

Several Irish businessmen as well as two Cuban-American congress members and an Irish-Cuban Yale professor registered

their strong discontent that this infamous revolutionary who

reportedly was responsible for the execution of thousands of Cubans

in the 1959 Castro-led revolution was being honored in this way. And

as if that wasn't enough, in the town of Kilkee, Co. Clare (where Che

himself once supposedly spent the night), the organizers of a local Che Guevara

festival have announced that his daughter, Aleida Guevara, had signed on as one of the speakers at their event to take place in

September 2012.

At the same time an article appeared in

the Irish press reporting about a poll that was conducted in the United Kingdom that ranked Michael

Collins to be Britain's second greatest enemy behind Mustafa Kemal

Ataturk (the Turkish nationalist military leader who defeated the

British in the war for Turkish independence). The article said that Collins even outranked Rommel, Napoleon and George Washington (curiously no mention of

Hitler). And there was not even a whimper about this in the Irish

press. That's probably because they knew that the wind would blow away

the memory of this poll in a month's time. But a physical memorial

will last longer than a poll, a lot longer. Was the Galway council

looking to attract more tourism to their area especially in

economically hard times? If so, could they not have found some other less

controversial way to promote their area's history and beauty? Of

course, but they probably believed that this move would undoubtedly

bring in more tourist money in the immediate future. What's not to

like about some extra cash in the coming years! Anyway, the monument has yet to be erected and probably never will.

So who was

Che Guevara? You have seen his caricature on millions of posters,

tee-shirts, tattoos and the like, all around the world. The Irish

graphic artist, Jim Fitzpatrick, first drew Guevara's figure (see above) in 1967

from a photo entitled “Guerrillero Heroico” (Heroic

Guerrilla Fighter) taken by Alberto Korda. It is this depiction of

Che that has become one of the most widely disseminated figures in

the modern world.

|

| Family tree on display in the Guevara home in Cordoba, Argentina |

And how was Che Guevara Irish? Che's

great grandfather Patrick Lynch, left Ireland for Argentina and

settled in Buenos Aires. He married Rosa de Galaya de la Camera, a

wealthy heiress and they had a daughter, Che's grandmother, Ana Lynch

born in 1851. She married Roberto Guevara Castro, and their eldest

son was Ernesto Guevara Lynch, Che's father, who was born in 1900 (the mother was 49 years of age when her eldest son was born???).

Ernesto married Celia de la Serna de la Llosa in 1927, and their

first child Ernesto, who would be known internationally as “Che”,

was born in Rosario, Argentina, in 1928. Young

Ernesto Guevara de la Serna Lynch was the eldest of five siblings.

His father, always proud of his Irish heritage, once commented

regarding his son's temperament that "the first thing to note is

that in my son's veins flowed the blood of the

Irish rebels."

|

| Che (left) with parents and siblings |

The Guevara family

created an intellectual atmosphere in their home, instilling in young

Ernesto a keen interest in literature, science and philosophy. As a

youngster he was a voracious reader and excelled in school. In 1948

he entered medical school at the University of Buenos Aires

graduating in 1953. His medical studies were interrupted for a

year-long motocycle journey through Latin America with his friend

Alberto Granado. On the trip he kept notes of their experiences which

he later wrote in book form entitled The

Motocycle Diaries. In later years it

became a New York Times best-seller and was made into a film by the

same name in 2004.

This trip brought the

young Guevara and his friend into contact with common people along

their route. In Chile they were exposed to the harsh life conditions

of workers in the copper mines. In Peru they saw dehumanizing poverty

among the peasants of the countryside and in a leper colony along the

Amazon River they saw the self-sacrifice and community spirit of

those who were outcast from the rest of society. These experiences

led Ernesto to analyse the conditions that were imposed by the haves

of society that compelled the have-nots

to live as they did. He felt that all people had the right to share

the earth's resources in such a way that they could all share a more

dignified life.

After he graduated from

medical school in 1953, Che decided to go on another trip north to

pursue his dream of creating a better world free from the grinding

poverty and inhumanity that he had witnessed on his first trip. This

journey took him through Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Panama, Costa Rica,

Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. In Central America he

came into contact with the extensive operations of the United Fruit

Company, and saw how they operated by taking control of the land

formerly farmed by poor defenseless peasants and was now employing

them for sub-human wages and offering no benefits.

In Guatemala, where

democratically elected President Jacobo Arbenz was expropriating

uncultivated lands and redistributing then to landless peasants,

Guevara liked what he saw and began to settle down. United Fruit

owned large tracts of uncultivated land and stood to lose a

substantial portion of their wealth from this land reform program.

Through United Fruit intervention, Arbenz was utlimately overthrown

by the CIA-assisted Guatamalan army. Prior to this, Che's Peruvian

economist girlfriend, Hilda Gadea, had introduced him to some Cuban

exiles living in Guatemala who were associated with Fidel and Raul Castro. But for the

moment his task was to stay out of the clutches of the new government

and so he sought refuge in the Argentine embassy until he could

obtain safe passage out of the country.

His next stop was Mexico City

where he made direct contact with the Castro brothers who were

planning to return to Cuba to overthrow the corrupt regime of

dictator Fulgencio Batista. After his Guatemala experience and

through long dialogues with Fidel Castro, Che came to a clearer

understanding that the struggle to establish the ideals he believed

in required even armed conflict. This was the key turning point in

Che's life and approach. His encounter with Fidel Castro, according

to biographer Simon Reid-Henry, led to a “revolutionary friendship

that would change the world.”

In November 1956, Guevara set

out with the Castro brothers and their band of 82 men on the Granma,

a small yacht they had purchased to cross from Mexico to Cuba.

Shortly after landing, the group was decimated by an attack of

Batista's soldiers. Sixty men were killed or captured leaving the

rest, including Guevara and the Castro's, to regroup again in the

Sierra Maestra mountains.

|

| On horseback near Santa Clara |

After almost two years in the Cuban

mountains skirmishing with Batista's army, Che was gaining the

confidence of the locals and recruiting many of them for his forces.

He was developing a military prowess that helped gain the upper hand

for the revolutionaries. His intuitive ability to overcome the enemy

was recognized by Fidel even though he was thought to take some wild

chances. His small band of men once stopped a Cuban army battalion of

1500 men by surrounding them and killing many of their soldiers.

Their campaign had progressed through

most of the provinces of the island nation until January 1, 1959 when

Batista, recognizing that his end was near, boarded a plane and fled to safety with more

than 300 million dollars. The next day Che Guevara and his forces

entered Havana and the revolutionary battle was over.

At first Castro placed Guevara in

charge of the purge of former Batista henchmen, including those

considered to be traitors, informants and other war criminals. His

sense of “revolutionary justice” compelled him to authorize the

execution of thousands after conviction by collective trials. He had

become a hardened man even before this when he personally executed

traitors and spies during his days in the mountains. His essay “Death

of a Traitor” in which he tells of how he personally executed

Eutimio Guerra, is clear evidence that Che, the man of high ideals

who at first struggled to uplift the dignity of the common man, had

now become a hardened aggressor. He himself wrote in a letter to his

friend, Luis Paredes Lopez, in Buenos Aires: “The executions by

firing squads are not only a necessity for the people of Cuba, but

also an imposition of the people.” It was here that many reasonable people who up to this point had admired him, now parted his

company. Mob justice held sway.

At different points in time Che held other important posts in the new revolutionary government. He was the head of the National Institute of Agrarian Reform, the head of the Cuban Literacy Campaign, the Finance Minister, the President of the National Bank, and the head of the Instruction Department of the Revolutionary Armed Forces. It was in this latter capacity that he trained many of the soldiers who repelled the CIA-financed Bay of Pigs invasion in April 1961 that attempted to overturn the Castro revolution. In addition, Castro sent Guevara on several diplomatic missions to the Soviet Union and the Eastern European communist bloc countries seeking aid for the continuance of their revolution.

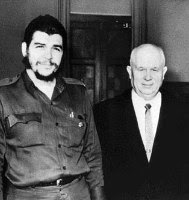

|

| With Khrushchev in Moscow |

In 1965 while on another diplomatic

mission that took him to several west African countries as well as to

Egypt, China and North Korea, Che also stopped off in Ireland and

celebrated St. Patrick's Day in Limerick City. He wrote to his father

with tongue-in-cheek: “I am in this green Ireland of your

ancestors. When they found out, the television came to ask me about

the Lynch genealogy, but in case they were horse thieves or something

like that, I didn't say much.”

As a result of this trip, Che was

re-directing his attention away from Cuba and becoming more

interested in exporting his brand of revolution to other countries.

Later that year, with a small band of Cubans, he went to the Congo

and collaborated with guerrilla leader Laurent-Desire Kabila. It

didn't take long for him to see that Kabila's men were undisciplined

and lacked the will to really make the revolution happen. He became

disillusioned and saw that his efforts were leading to failure. He

summed it up in the words: “we can't liberate by ourselves a

country that does not want to fight.”

Che now felt that he could no longer

return to Cuba because he had submitted his written resignation from

all his government posts to Fidel Castro and had renounced his Cuban

citizenship. Fidel read this letter to a rally in Havana, an act

which, in Che's mind, solemnized his separation from Cuba.

He next turned his attention to South

America and to Bolivia in particular. With his band of 50 men Che

scored several early successes in his battles against the Bolivian

army in early 1967. However he did not know that the US had been

tipped off about his new revolutionary effort and was sending CIA

special operatives into Bolivia to counteract him. This factor, in

addition to his inability to recruit support from the locals in the

Vallegrande area, put him at a serious disadvantage. On October 8,

1967, with the intelligence and support of these CIA operatives,

Bolivian troops captured Che. He was taken to La Higuera, to a small

schoolhouse where he was held until the next day when he was executed

by a Bolivian army sargent on the orders of Bolivian President Rene

Barriento.

Che's body was buried in an unmarked

common grave where he lay for 30 years. In July 1997 a team of Cuban

and Argentine specialists uncovered the grave finding seven bodies. By

matching dental records still on file in Cuba they were able to

identify the skeletal remains of Che Guevara. Subsequently his

remains were moved to a mausoleum in Santa Clara, Cuba where under

his command, his forces had dealt the decisive blow to the Batista

regime in 1959.

"He who lives by the sword will die by the sword."

Matthew 26:52

No comments:

Post a Comment